Photo by Sebastian Herrmann on Unsplash

Finding a test engineer who would not have heard of version control systems is difficult nowadays. Some have worked (and work with quite “old”) - such as Subversion, Mercurial HG, etc.

But the vast majority of modern projects today use Git. If you need to download a “fresh” version of the product code or automated tests, go to the Terminal (or GUI tool) and perform a git fetch or git pull.

Learning the basic Git commands is not that hard. It is a bit more difficult to understand what merge and rebase are (and their difference).

But few engineers look deeper - how does Git work “under the hood”? Of course, you don’t have to know this to use Git. But I was still interested to understand. Plus, if you will be asked about Git internals at the interview - you will already know it! (But why ask such a question???).

Welcome to the world of graphs and hash functions. You can learn about another application of hash functions - Merkle trees - in my previous post.

A bit of Git theory

Let me remind you what a typical workflow with Git looks like:

- Make a clone of a remote repository:

git clone https://somerepo - Make a branch for your changes (fixes, tests, etc.):

git checkout -b fix/autotests - Write everything you want (Git will notice it but wait for your actions):

git statusreturns “changes not staged for commit.” - Add files to staged area using:

git add - Create a new commit:

git commit -m "Fix autotests" - Send prepared commit to a remote repository:

git push origin fix/autotests - Pass the code review and merge the changes into the main branch:

git rebaseorgit merge - Send changes to the main branch from the local repository to the remote one:

git push origin main/master - Remove the branch, if necessary:

git branch -D fix/autotests

The structure of Git

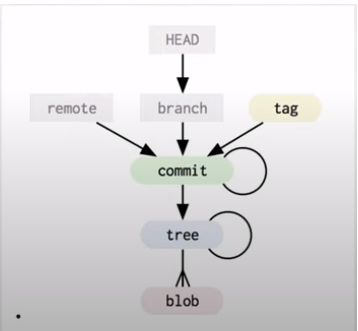

There are three types of objects that Git takes care of:

- Commit - contains the author of the commit, date, message, and pointer to the tree of changes. Also, each commit has one (or more) parent commit;

- Tree - contains a pointer to other trees and specific blob objects;

- Blob - specific data (source code files, pictures, videos, etc.)

So what is the structure of the Git repository? This is a data structure called a graph. Or, more specifically - a directed acyclic graph.

Where can all this information be found? When you clone a repository or create a new one, all this data will be stored in a hidden .git directory in the project.

What are tags and branches? These are just pointers to a commit object.

What happens during git init?

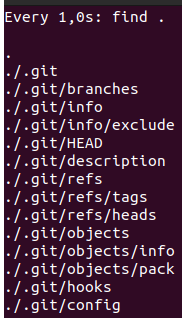

Let’s create a new repository in the directory - testrepo. To do this, go to the folder and run the command git init.

As a result, we get a lot of exciting things in the .git directory:

Making a first commit

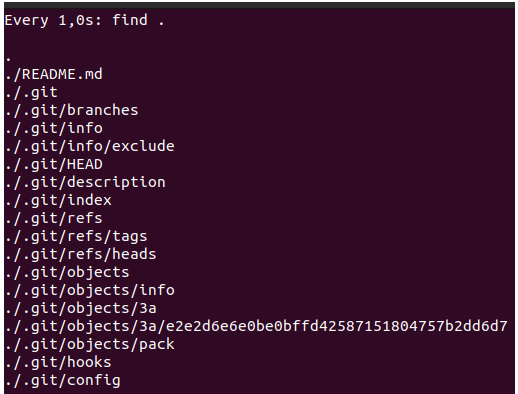

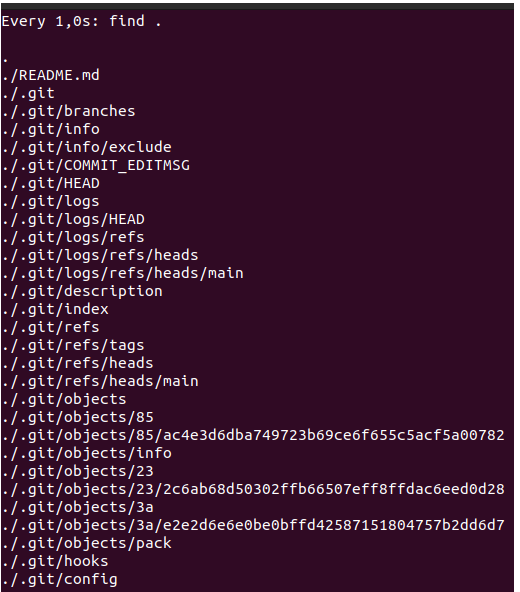

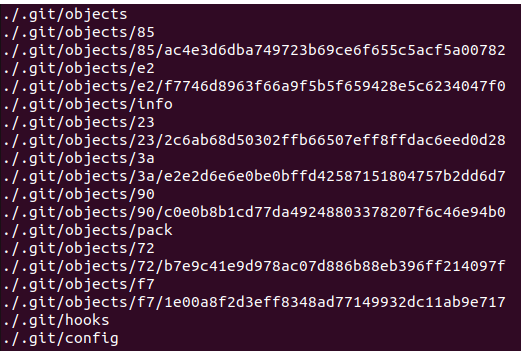

Create a new README.md file with any content and add it to the first git add. Now, .git looks like this:

We can see that Git created some new folders and files: 3a folder with a strange file inside.

It results from the SHA-1 hash function running on our README.md file. (You can read about the hash functions in one of my previous blog posts)

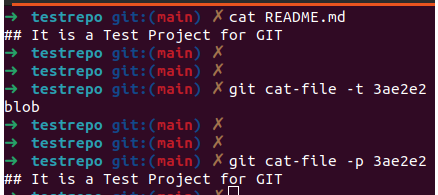

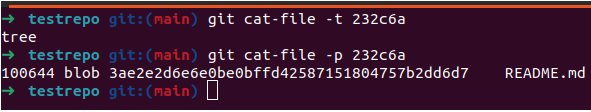

Git has a separate team to help us with research: git cat-file.

-targument indicates the type of object-pargument shows the contents of the object

Note: You may specify not the full hash of the object - but only the first six characters (Keep in mind that you must also set the subfolder characters - in our case it is 3a. And then the first four characters of the object)

In our case, the results will be as follows:

When we added the README.md file to the staging area, Git also created a blob object under the hood.

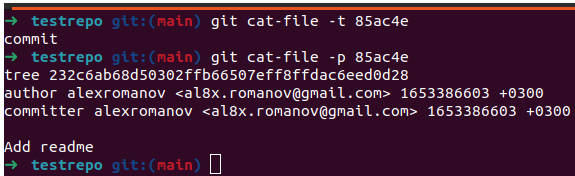

Next, create a new commit with the file and look at the contents of the .git directory again.

As you can see, now we have not one new object but three. One we have already seen (starts with 3ae2e2). What about others?

232c6a is a tree object. It points to a blob object (we also see the hash of this object and the name). 100644 is the permissions for this file.

85ac4e is a commit object. It points to an object of type tree (we see its complete hash) and indicates the author and the text of the commit.

More commits

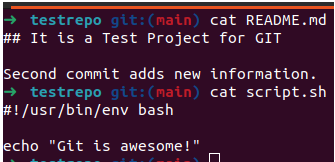

To complete the task - add another file and correct README.md.

.git contains new objects:

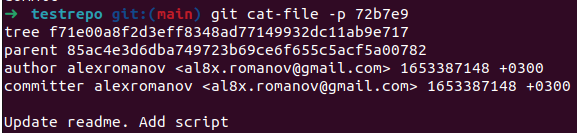

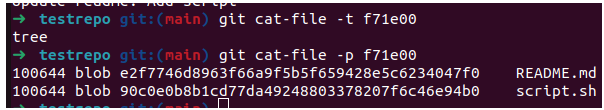

First, we have a new commit object that contains a pointer to a new tree object, f71e00a8f2d3eff8348ad77149932dc11ab9e717.

In addition, in this commit we have parent 85ac4e3d6dba749723b69ce6f655c5acf5a00782

If we look at the new tree, we will see that it now points to two objects of type blob: a new file and a modified README.md.

Interestingly, the blob object for README.md already has a different hash. The reason is that we changed the file’s text - so the hash value also changed. But the old blob file also remained available (3ae2e2)!

A few words about the branches

Finally, I want to show what happens when we create new branches in Git.

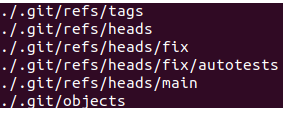

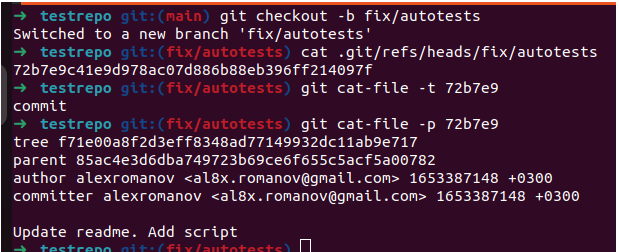

Let’s run the git checkout -b fix/autotests command and look in .git.

If we look at the contents of the .git/refs/heads/fix/autotests file, we will see that it points to our second commit!

Conclusions

As you can see - Git under the hood looks not so complicated. Especially when you already know what hashing is.

Therefore, the next time you see unknown numbers and letters near commits, you will know that it is a just hash value from objects.