Photo by Robynne Hu on Unsplash

This is the sixth blog post in the “Blockchain for Test Engineers” series.

We have explored concepts from hashing, encryption, and distributed systems in the previous posts. Now it’s time to apply this knowledge and understand what blockchain is.

When I first started to google on this topic, I found many articles, videos, and even courses dedicated to the blockchain. But all these resources eventually fell into two categories: too superficial or too deep. There was nothing in between.

Today I want to briefly, technically, and with pictures, tell you what blockchain is and how it works. We will save questions of advantages and disadvantages and other deep technical details for another time.

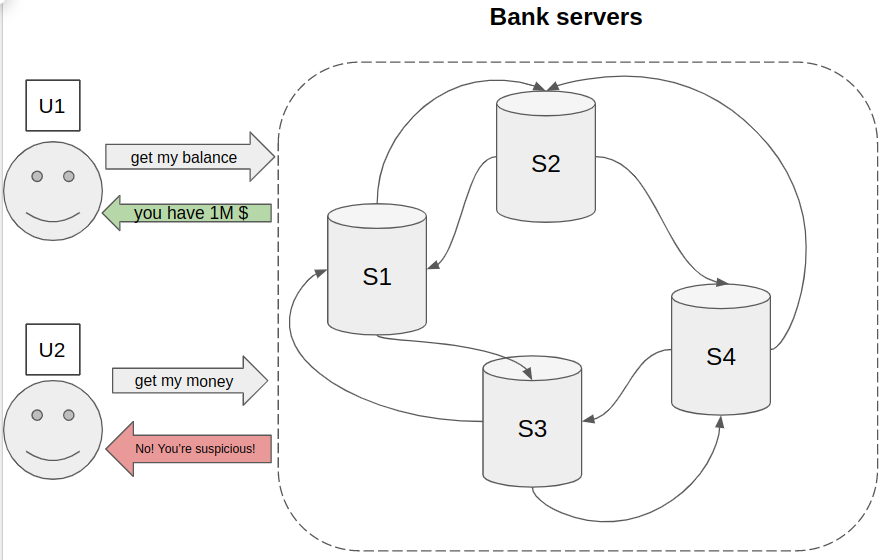

Why do we need a blockchain if there is already a bank?

Each of us uses the services of a bank and makes transactions from a card or account. We can see the list of transactions by going to the bank’s application. (Or by requesting in paper form as a reference).

Each transaction contains information about the time and purpose of the payment. In addition, we can also see the recipient of each transaction.

Two parties can see this list of transactions - you, as a client of the bank, and the bank itself. The bank “securely” stores the information about your transactions on the bank’s servers. By receiving this list, you trust the bank that it did not inadvertently manipulate your balance.

In addition, the bank has every right to freeze your funds if it considers them suspicious.

Don’t you think that requires a lot of trust and single-handedly manages your accounts?

What is blockchain?

The original idea of blockchain emerged as an alternative to regular bank payments. (Of course, the blockchain is not only used for financial transactions - but let’s start with them).

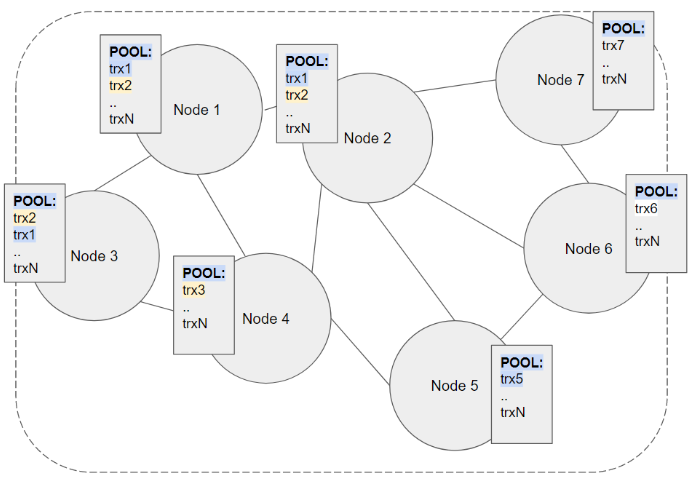

Instead of the bank servers, we have a peer-to-peer network of thousands of computers. Each node in the network contains an entire history of transactions made by all users in the system. As transaction data is stored on multiple nodes simultaneously, nobody can “freeze” your money or delete transaction history.

The nodes in the network share information about transactions with each other. So the state of the transaction history is synchronized.

Another key difference from regular banking is that transaction history on the blockchain cannot be changed and is visible to anyone.

How does it work technically?

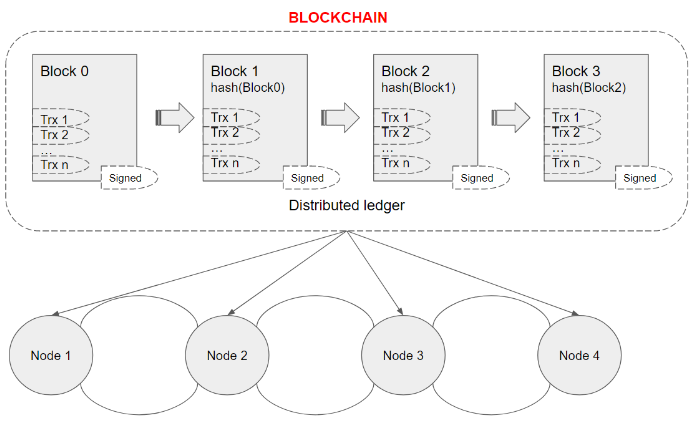

We can think about transaction data on each node as a form of a distributed ledger (or, in other words - an extensive distributed database of data). The ledger here means that information contains a few critical components: who send the money, to whom, and which amount.

The ledger is a set of identical blocks (that are linked cryptographically) and distributed across all nodes in a peer-to-peer network.

Each block has four fields: block size, block headers, transaction counter, and transactions.

The block headers contain:

- the block version;

- the hash of the previous block. The blockchain is named so - it is a chain of blocks;

- the Merkle root hash of all transactions included in the block;

- timestamp;

- difficulty target;

- nonce;

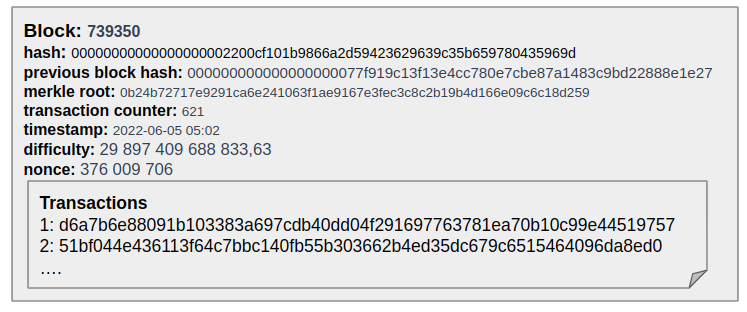

Why store the hash of the previous block?

Here is the beauty and power of the hashing. It helps to ensure the consistency of the blockchain and prevent changes.

Imagine that an attacker wants to change the content of a transaction that belongs to block one. The change in the transaction will change the hash of the transaction. Then the change of transaction hash will change the hash of block one. If an attacker wants to spread a new block across the network, he must modify the other blocks after block one. (because they are linked).

In addition - the attacker then needs to spread a new chain of blocks (modified) across all the nodes and force everybody to use an updated version of the chain. Given the number of nodes in the network, it can be a challenging and expensive task. Why expensive? An attacker needs to re-create many blocks, which takes resources and time.

Every block and every transaction are digitally signed. Any network user can verify this signature and ensure there were no fakes. So it will be suspicious if all blocks in the “attackers chain” are signed by a single user.

How user creates a new transaction

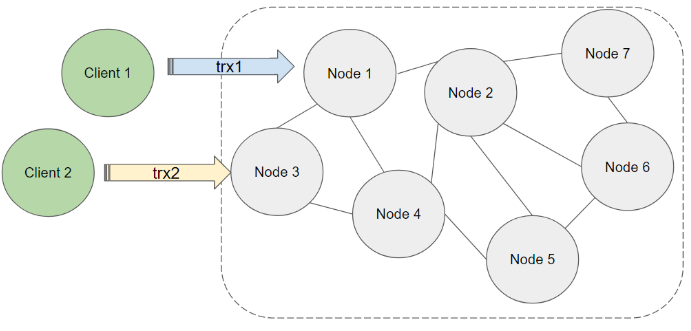

The client forms a transaction using the command line or special applications (crypto wallets). Inside a transaction, there are sender, recipient, and the transfer amount. In addition, he sets the transaction fee. (We will see different transaction models in the upcoming blog posts).

In our example, client one connects to node one and sends trx1, and client two sends trx2 to node three. The client has no control over which node it connects to and where it sends the transaction.

Each network node collects incoming transactions for some time in its local storage (MemPool). Nodes exchange incoming transactions with each other (but it is not mandatory. Nodes can be at any place in the world and have different configurations - so the view of the network can differ from node to node).

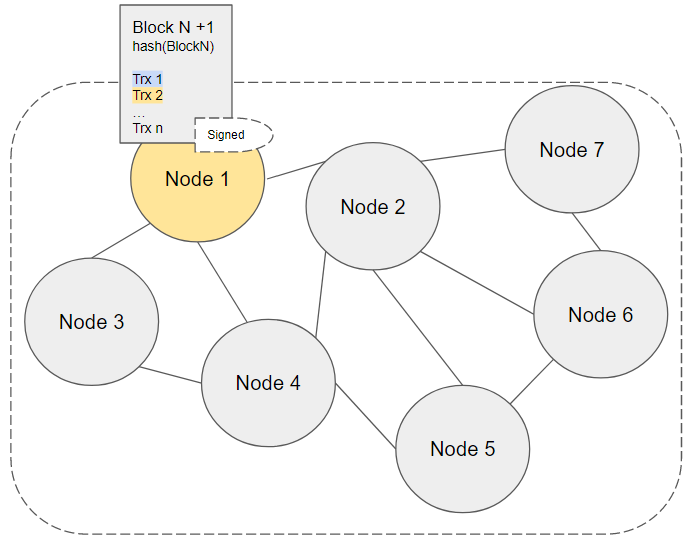

From time to time, the node forms a new block of transactions. The node signs the block. In addition, to finally create and distribute a valid block in the network, the node must participate in the Proof-Of-Work consensus.

Mining new blocks

Each node with a new potential block starts a race with the other nodes who prepared a candidate block. The ultimate goal of each miner node is to make a special kind of block hash. For example, it can be a certain amount of zeroes at the beginning of the hash value.

The miner adds a number (nonce) to the block to find such a hash. If the hash is not equal to the desired one - the miner increments the nonce and does it again. This task is simple but resource-intensive - you need to make a tremendous amount of trial and error by brute force. This process is called mining.

The first node that finds the correct nonce and sends the block to the network - receives a reward in coins plus optional fees from each transaction. The reward is not immediately accessible to the user but only after adding some amount of new blocks.

Block validation

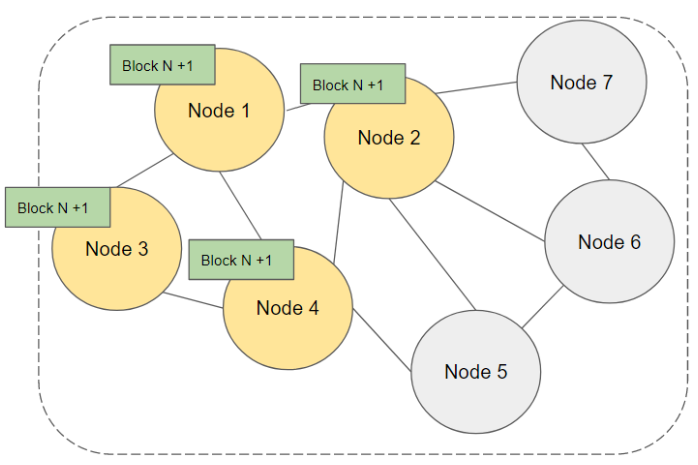

When a node finds such a nonce, it sends a new block to other nodes in the network. The node that receives the new block validates it and all transactions inside.

What is checked inside a block:

- block structure

- block header hash is equal

- block timestamp

- block size

- the first transaction is a coinbase? (Coinbase transaction transfers the reward to the miner - it is always first in the block)

- all transactions within the block

If everything is in order with the block - it starts to spread over the network as a new valid block.

Block propagation

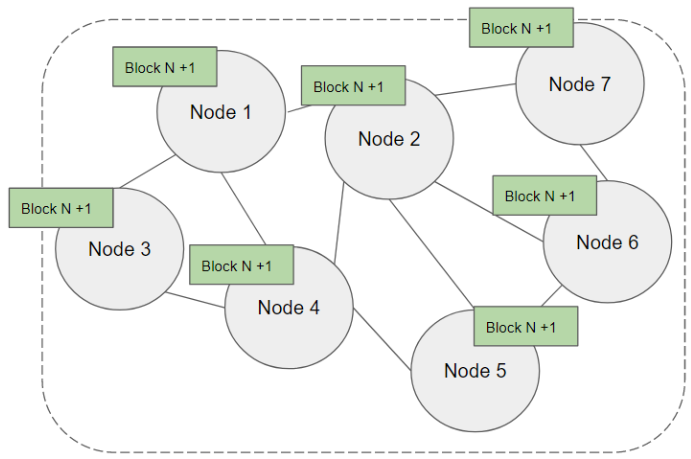

Sooner or later, nodes will distribute the new block over the network using some protocol (for example, it can be Gossip protocol).

In Bitcoin, a new block appears on the network every 10 minutes (the internal mining algorithm checks the complexity of the mining for all peers and adjusts it every 2048 blocks). But this does not mean at all that your transaction will be in the block in 10 minutes. But more on that next time.

After some time, each node in the network gets the latest mined block. In parallel, other nodes can mine the subsequent candidate blocks.

What you need to consider when testing the blockchain

- the blockchain networks are huge

- the blockchain networks are always in a working state

- each change in the network affects many users

- you can’t modify the data once saved on the blockchain

- the information you save on-chain during testing is visible to anyone

I hope that now you have a general understanding of the blockchain. We will gradually delve into different parts of this enormous system and see which thing we can test in the following blog posts.